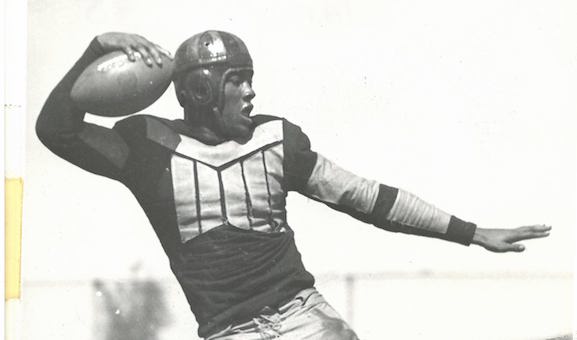

The legend of Ozzie Simmons is always worth celebrating whenever Iowa faces Minnesota

By Pat Harty

IOWA CITY, Iowa – The football rivalry between Iowa and Minnesota will forever be linked to the legacy of Ozzie Simmons, and sometimes we need to be reminded why.

We need to be reminded heading into Saturday’s game at TCF Bank Stadium in Minneapolis that the battle for Floyd of Rosedale, and the statue of a beloved bronze pig that goes to the winner, is rooted in racism and violence, but is also an example of how sports can help good triumph over evil.

We need to be reminded that Ozzie Simmons is one of the most important players in the history of the Iowa program because he stands for so much more than his football prowess.

Simmons was a black man playing in a white man’s game in the 1930s, and sadly, many weren’t willing to accept that and they lashed out in ways that are deplorable and disgusting.

The fact that Simmons was an outstanding running back with moves that often left defenders grabbing for air only made the situation worse because some were outraged that a black man was excelling in a sport dominated by white men.

Iowa’s game against Minnesota in 1934 was especially brutal as Simmons was knocked out of the game three times due to injuries.

Minnesota rolled to a 48-12 victory, but its physical abuse of Simmons, and that it was allowed by the officials, was the main storyline to come from the game.

"The Minnesota game was the most blatant attack,” Simmons said in a 1989 interview. “They were blatant with their piling on and kneeing me. It was obvious, but the refs didn't call it. Some of our fans wanted to come out on the field.”

The tension between the two schools had reached a disturbing level with Iowa preparing to host the Gophers a year later in Iowa City.

Iowa Governor Clyde Herring issued an ominous warning in the days leading up to the game.

"If the officials stand for any rough tactics like Minnesota used last year, I'm sure the crowd won't,” Herring said.

Minnesota's coach Bernie Bierman was so concerned about safety that he requested extra security for his team.

To help defuse the situation, Minnesota Governor Floyd B. Olson wagered Herring a prize hog that the Gophers would win the game, which they did 13-6 without incident.

And that led to the birth of Floyd of Rosedale as current Iowa running back Mekhi Sargent will share with his teammates on Wednesday after having researched Floyd's tradition.

Sargent will learn through his research that the original Floyd was a full-blooded champion hog that Herring shipped to Olson after the loss in 1935. Olson then presented it to the University of Minnesota after commissioning Charles Brieschi, a St. Paul sculptor, to create a bronze likeness of the hog.

Sargent was picked to give the presentation, which occurs before each of Iowa’s four trophy games, because he is new to the team after spending his freshman and sophomore seasons at Iowa Western Community College.

Sargent is also from Key West, Fla., where Iowa’s tradition in football is far from being a hot topic, if it’s a topic at all.

“Mekhi, he got nominated by his peers. Who am I to say no?” Iowa coach Kirk Ferentz said at his weekly press conference on Tuesday. “And it makes sense. The guys picked him last night. They probably figure he's about from as far away as anybody on our football team right now, really knows probably less about Floyd than anybody. So it's good. If he screws something up somebody will correct him, I'm sure.”

Ferentz is ultimately judged by Iowa’s success on the field, but he does so many other things behind the scenes that also make him a good leader.

Each of Iowa’s four trophy games against Iowa State, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Nebraska are special in their own way and Ferentz does what he can to embrace the history and tradition.

My two favorites are Floyd of Rosedale and The Heroes Trophy, which goes to the winner of the Iowa-Nebraska game and honors one citizen from each state who are admired for their bravery and nobility.

Floyd of Rosedale honors Simmons, who passed away in 2001, for his bravery and toughness, and deservedly so, because Simmons experienced a level of pain, suffering and humiliation that nobody should ever have to endure.

But thanks to the support system at the University of Iowa, and to its willingness to give chances to African-Americans when most other schools and athletic rosters were segregated, Simmons not only persevered, but thrived as a Hawkeye.

Simmons led Iowa in rushing as a junior in 1935 and was selected first-team All-America for an Iowa team that finished 4-2-2 overall.

He had five touchdown runs of at least 50 yards during the season and rushed for 192 yards and had an interception during a 19-0 victory over Illinois.

Simmons’ slippery running style earned him the nickname the “Ebony Eel,” which was meant as a compliment, but some would consider insensitive by today’s standards.

Simmons led Iowa in rushing as a senior in 1936, but the Hawkeyes failed to win a conference game and were crushed by Minnesota, 52-0.

Simmons left the team briefly in the wake of the Minnesota loss, but returned for the final two games against Purdue and Temple.

He capped his brilliant career with a 74-yard touchdown run during Iowa’s 25-0 upset of Temple, which was coached by the legendary Glenn “Pop” Warner at the time.

Simmons stayed the course despite his course being littered with obstacles and trash that are so far removed from today’s society.

Simmons came to Iowa a decade after the death of Iowa State legend Jack Trice in 1923. Trice died from hemorrhaged lungs and internal bleeding as a result from injuries suffered in a game against Minnesota.

His teammates accused the Minnesota players of targeting Trice, who was black, because of his skin color.

Thankfully, it never reached that point with Simmons because cooler heads ultimately prevailed.

The first few pages in any book about the history of the Iowa football program should make mention of Ozzie Simmons because of what he stands for as a student-athlete who refused to back down against racism, and because the University of Iowa stood with him at a time when that was highly unpopular.

Minnesota clearly is on the wrong side of history with regard to Floyd of Rosedale, but it was a Minnesota governor that laid out the plan for peace by wagering a pig.

So both sides helped to create what is arguably the best trophy game in all of college football, but there wouldn’t be a Floyd of Rosedale without the impact of Ozzie Simmons.

His life changed forever after an Iowa graduate saw him play in high school and suggested that he check out his alma mater where blacks, including the legendary Duke Slater, had been team members since 1895.

Simmons liked what he heard about the University of Iowa’s willingness to embrace racial equality, so he and his brother, Don Simmons, boarded a train to Iowa City and the rest is history that thankfully gets recognized whenever Iowa and Minnesota square off in football.

Mekhi Sargent will have learned about a determined and courageous young man by the time he gives his presentation on Wednesday. Sargent should be inspired by the legacy of Ozzie Simmons and grateful for what Simmons was willing to endure.

The current times are far from perfect when it comes to racial equality. But we’ve also come a long way as a society, thanks to courageous people like Ozzie Simmons, who withstood a raging storm of hate and bigotry just to better himself.