If ever a year to tell story of Floyd of Rosedale, this is the year

By Pat Harty

IOWA CITY, Iowa – In early June, when multiple black former players started accusing the Iowa football program of having racial disparities, a once-proud tradition and inclusive culture was suddenly on the wrong side of the racial narrative.

The accusations of mistreatment were in stark contrast to Iowa’s history of being on the right side of divisive racial issues.

The Iowa football program in many ways has been a pioneer when it comes to racial equality, awareness and acceptance, and that only adds to the disappointment and shame with the current situation.

But Iowa’s history also serves as hope that the current controversy will be dealt with properly, and that the real Iowa Way, the one in which black players were allowed to compete at a time when most schools strongly opposed it, will ultimately prevail again.

Iowa’s history won’t fix the current problems, but it could help with the challenge of moving forward by reminding fans and critics about all the good and noble causes that have been waged on behalf of racial equality over the years.

That comes to mind with Iowa preparing to face Minnesota on Friday night in Minneapolis.

“Floyd was in the weight room, so I think that was a good reminder just that this is a rivalry game,” said Iowa coach Kirk Ferentz. “Every game is important. Every win means a lot but it’s just a reminder that this one typically is very hard fought and nobody owns the trophy.

“You get to keep it for a year, or this time maybe less than a year, a day less, but nonetheless it’s a one-year rental, so it’s up for grabs again Friday.”

Both teams, in addition to trying to avoid falling to 1-3, will also compete for the privilege of having Floyd of Rosedale in their trophy case for the next year.

Floyd is the statue of a bronze pig that goes to the winner of this border rivalry, which has been heated and violent at times.

Floyd’s origin is rooted in hate and prejudice, and it came to be as way to avoid violence between the two fan bases.

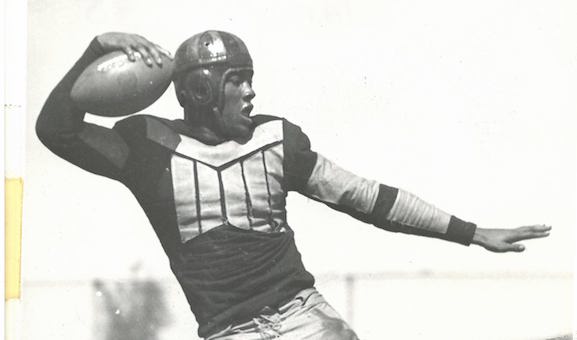

The story has been told over and over, but it’s always worth telling again, the story about Iowa running back Ozzie Simmons suffering one cheap shot after another during a 48-12 loss to the Gophers in 1934. Simmons was singled out for abuse because he was a black man playing what was considered a white man’s game in most places at the time.

The physical and verbal abuse to which he was subjected on the field was so obvious, so persistent and so blatantly racist that tensions still were high nearly a year later heading into the rematch in Iowa City.

With the 1935 game approaching, and with the threat of violence increasing, Governor Floyd B. Olson of Minnesota and Governor Clyde Herring of Iowa made a friendly wager on the game’s outcome.

The bet was described as a diplomatic move to lessen the friction between the two fan bases, and the winner would be awarded a full-blooded champion hog from the loser.

Minnesota edged the Hawkeyes 13-6, and thankfully, the bet kept emotions from boiling over.

Following the game, Governor Herring shipped the live hog to Governor Olson, and that marked the beginning of Floyd of Rosedale.

A bronze likeness to the real thing was then created by St. Paul sculptor Charles Brieschi and that statue will be on the Iowa sideline during Friday’s game.

Should Minnesota beat Iowa for the first time since 2014, the Minnesota players, as soon as the game ends, will rush over to the Iowa bench to get the pig, even during a global pandemic.

Floyd of Rosedale is that important because it stands for so much more than just winning a football game.

It stands for right versus wrong and good versus evil, and fortunately, Iowa made the right stand in this case, and in so many other cases dealing with race.

Ozzie Simmons was an electrifying running back, but because of his skin color, most schools didn’t recruit him out of Fort Worth, Texas.

Iowa was an exception, and had been for a while.

Tipton native Frank Kinney Holbrook was the first African American intercollegiate athlete at the University of Iowa and one of the first African Americans to participate on an American college varsity athletic squad.

He played on the Iowa football team and lettered in both football and track in 1895 and 1896. He was Iowa’s leading scorer in 1896 and led the Hawkeyes to their first football conference title in school history.

To help put that in perspective, running back Wilbur Jackson was the first black player to be offered a football scholarship from Alabama, where he played from 1971-73, or, in other words, more than 70 years after Holbrook played for Iowa, and more than 30 years after Simmons had played for the Hawkeyes.

Iowa’s past isn’t without some racial controversy, however.

The 1969 spring boycott by 16 black players came at the end of a decade in which the civil rights movement and black power struggle had been building across the nation.

The boycott hurt the program in so many ways from a personnel, and from an image standpoint, and it took some time to recover, on and off the field.

Iowa did recover, though, and less than a decade later, Hayden Fry was hired to coach the Hawkeyes.

Fry had broken the color barrier in the Southwest Conference by recruiting Jerry LeVias to Southern Methodist University in the mid-1960s. It was not a popular decision at the time, but it was the right thing to do.

LeVias, much like Simmons, was mistreated and subjected to racism, but he persevered, thanks largely to Fry’s commitment, courage and unwavering support.

As for the current situation at Iowa, too many black former players have made accusations of racial disparities to where it would be naïve, misguided, and frankly, racist to dismiss them all.

Kirk Ferentz even has admitted to having a blind spot, while the Iowa culture was accused of having rules that were racially and culturally bias, according to the Husch Blackwell report that was released in late July.

Eight former black players also are preparing to file a lawsuit after Iowa refused to meet their demands, which included the removal of Kirk Ferentz, Iowa offensive coordinator Brian Ferentz and Iowa Athletic Director Gary Barta, and $20 million in compensation.

So just like in 1969, the Iowa football program has problems with race that have to be fixed, and that are being fixed, according to Kirk Ferentz.

Assuming that Kirk Ferentz brings up Floyd of Rosedale this week as a way to motivate his players, hopefully, he will take the time to tell the full story to his players.

Because the full story sends a powerful message and would remind the players what they truly represent as Hawkeyes.