Iowa football should embrace its past to help change the culture

By Pat Harty

IOWA CITY, Iowa – When it comes to racism, the past is usually what brings shame and disgust.

The past is when blacks couldn’t vote, when segregation ruled and when college sports was as white as cotton.

But there were exceptions on the college landscape, including the University of Iowa, which for over a century has been at the forefront in promoting racial equality through athletics.

That’s not an opinion.

It’s a fact.

Kinney Holbrook made history when he joined the Iowa football team in the fall of 1895. The Tipton native became the university’s first African-American football player, and among the first in the nation.

To put that in perspective, Wilbur Jackson was the first black player to be offered a scholarship from Alabama, where he played running back from 1971-73 under the legendary Bear Bryant, and nearly 80 years after Holbrook had played for Iowa.

By the early 1970s, Iowa had provided opportunities to countless black players, from Holbrook to Duke Slater to Ozzie Simmons to Calvin Jones to Frank Gilliam to Eddie Vincent to Bob Jeter to Willie Fleming to Wilburn Hollis to Silas McKinnie to Larry Ferguson to Levi Mitchell, and that’s just the prominent black players.

Slater played tackle at Iowa from 1918-21, and did so without wearing a helmet, which has since added to his legend. He also played 10 seasons in the NFL and was the first black lineman in league history.

Slater would go on to become just the second African-American judge in Chicago history and served in that role for nearly two decades until his death in 1966.

That isn’t to say it’s been total racial harmony up until the current controversy in which numerous former black Iowa players have described a culture of racial disparities and bullying within the Iowa football program under veteran head coach Kirk Ferentz.

Chris Doyle is at the center of the of accusations, and Iowa’s former strength and conditioning coach agreed this past Sunday to a separation package that will pay him $1.1 million and cover his family’s medical expenses for 15 months.

Doyle also agreed to not pursue legal action as part of the separation.

His departure was just the start of a long and painful process that includes an independent review that is currently being conducted by a law firm from Kansas City, Mo.

“There’s still a lot of difficult conversations to have,” said Iowa Athletic Director Gary Barta. “There have been some really difficult conversations so far.”

Iowa has dealt with racial unrest before, most notably the black boycott in 1969 when 16 African-American football players, including eight lettermen, boycotted spring practice under head coach Ray Nagel.

The civil rights movement was raging and the Iowa campus was no exception.

The players were upset over how two other black players on the team had been disciplined by Nagel, and their anger quickly turned into a movement on campus.

Seven of the 16 black players were ultimately reinstated to the team, but Nagel would last just two more seasons as Iowa finished 5-5 in 1969 and 3-6-1 in 1970 before he was fired.

The next 10 years would be some of the bleakest in program history as the Iowa football team sunk to near the bottom of the Big Ten in the 1970s, the low point being a disastrous 0-11 season in 1973.

It wasn’t until Hayden Fry was hired as head coach shortly after the 1978 season that the misery finally started to end.

Fry had a reputation for rebuilding downtrodden football programs, and he was also a pioneer in regard to racial equality.

Fry broke the color barrier in the Southwest Conference by recruiting Jerry LeVias to play for Southern Methodist University in the mid-1960s. It was an unpopular move that took, courage, resolve, vision and character.

Fry broke the color barrier in the Southwest Conference by recruiting Jerry LeVias to play for Southern Methodist University in the mid-1960s. It was an unpopular move that took, courage, resolve, vision and character.

Fry also recruited and coached numerous black players during 20 seasons as the Iowa head coach. He and his assistant coaches built recruiting pipelines that flowed from Texas and from the New York-New Jersey area, and with that came some of the greatest black players in program history, including Andre Tippett, Owen Gill, Ronnie Harmon, Devon Mitchell, Merton Hanks and Leroy Smith.

Fry was the perfect hire in so many ways. His football acumen was matched by his belief that all people were created equal, and that belief carried to sports.

That belief has been part of the Iowa way for over a century, and that’s why UI officials should reconnect to the past as they try to change the current culture and the image of the Iowa football program.

The past doesn’t excuse what allegedly has occurred under Kirk Ferentz. But it gives hope that things will get better because Iowa has a history of promoting and practicing racial equality.

Iowa has a history of being on the right side of stories that involve sports and racism.

Iowa took what was considered a radical step in 1983 when it hired George Raveling to coach the men’s basketball team and C. Vivian Stringer to coach the women’s team.

It was almost unheard of at the time for a Division I school to have a black head coach, and for Iowa to have a black head coach in two major sports was significant.

It was the latest in a long-list of examples in which the University of Iowa helped to promote racial equality and spread awareness.

Iowa needs to embrace its past as it tries to learn from the current controversy and then move forward.

Iowa needs to be proud of its past because it deserves respect and admiration.

However, the fact that the Iowa football program is now being placed under a microscope due to accusations of racial disparities by numerous former players shows how quickly an image that took decades to build can be tarnished.

It only takes a few bad apples to damage what so many others helped to build over time.

Iowa and Minnesota have been competing for Floyd of Rosedale since 1935 in football and the origin of this traveling trophy is rooted in racism.

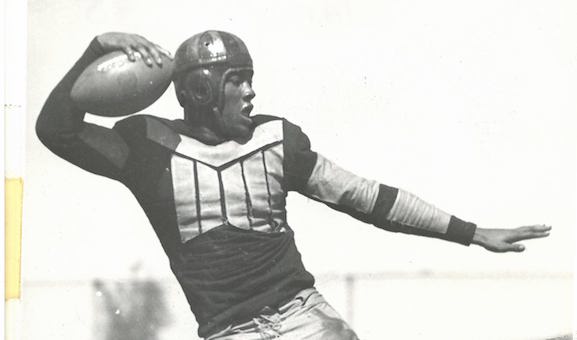

Tensions between the two border rivals had been escalating due mostly to the verbal and physical abuse that Iowa running back Ozzie Simmons had to endure during the 1934 game in Minneapolis.

In addition to being Iowa’s star player, Simmons was one of few black players competing in college football at the time, and that didn’t sit well with the Minnesota players and fans, and with much of the nation.

So in order to calm tensions heading into the 1935 game in Iowa City, a bet between Minnesota Governor Floyd B. Olson and Iowa Governor Clyde Herring gave birth to Floyd of Rosedale.

After Iowa’s 13-6 loss, Herring presented Olson with Floyd of Rosedale, a full-bloodied champion pig.

Floyd has since been transformed into a statue of a bronze pig that goes to the winner of the Iowa-Minnesota game.

But Floyd stands for so much more than a football game. He stands for racial equality and is a key piece of history in which the University of Iowa has reason to be proud of its role in the story.

The Iowa football program has a serious problem that has to be fixed, while the 64-year old Kirk Ferentz in some ways is fighting to save his once-proud legacy.

Ferentz needs to embrace Iowa’s tradition of racial equality and use it to help fuel change.

He needs to look to the past as a way to address the present because the Iowa football program, and the University of Iowa, both deserve better.