Devine: Saturday is a special day for my family and me

By Tyler Devine

IOWA CITY, Iowa – I’ve been waiting to publish this story for quite some time.

Saturday is a special day for my family and me. Sometime during No. 3 Iowa’s matchup with No. 4 Penn State, the 100th anniversary of the 1921 Big Ten champion Iowa football team will be honored, and a throng of close and extended family will be in Kinnick Stadium to witness it.

While growing up, I was regaled with countless stories of the 1921 team under coach Howard Jones, who had led the Hawkeyes to a combined 16-6-1 record over the previous three seasons but had yet to make the breakthrough he would during that season.

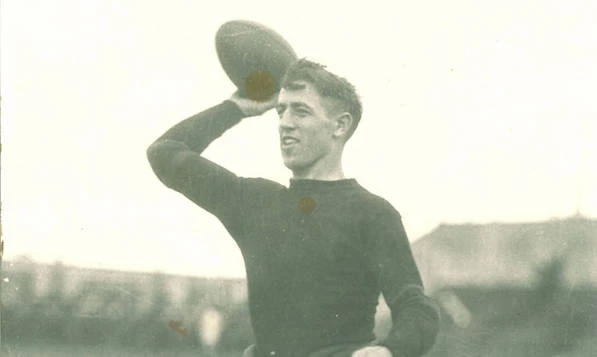

My great, great uncle Aubrey Devine, and my great grandfather Glenn Devine were part of Iowa’s starting 11 during this storied season – Aubrey the headline-grabbing quarterback and Glenn a behind-the-scenes halfback. Both also played defense. The roster was full of Hawkeye legends – Gordon Locke, Lester Belding and the barrier-smashing Duke Slater.

Nearly a century ago, on a blustery October day in Iowa City, the legend of Iowa football’s first Big Ten championship team was born.

An estimated 8,000 fans – bodies draped in overcoats, fedoras and flat caps atop their heads – flocked to Iowa Field to watch their beloved “Old Gold” beat the vaunted Fighting Irish of Notre Dame 10-7 in the first-ever meeting between the teams.

Penn State isn’t exactly early-1900s Notre Dame and James Franklin isn’t exactly Knute Rockne, but it seems fitting that the 1921 team is being honored at what might be the biggest game in Kinnick Stadium since top-ranked Iowa beat No. 2 Michigan 12-10 in 1985.

To celebrate that victory over the Irish, Hawkeye fans set ablaze barrel staves and an old piano box at the corner of Clinton and Washington in downtown Iowa City. Some tried to rush the Englert Theatre but were held off by two police officers.

In the Devine family, I can’t recall another game from that mythical season coming up in conversation more than Iowa’s battle with the Irish. The Hawkeyes began the season with a 52-14 rout of Knox College, while Notre Dame dismantled its first two opponents by a combined score of 113-10.

Notre Dame was the overwhelming favorite, and rightly so. The Irish were on a 20-game win streak and were two-time defending national champions (depending on who you asked in those days before a championship or playoff system) under legendary coach Knute Rockne, who popularized and revolutionized the forward pass as both a player and coach.

Rockne thought even further outside the box for the showdown in Iowa City, dressing his players in green uniforms for the first time in an effort to make receivers more visible to passers against Iowa’s black uniforms with vertical gold stripes across the torso.

An unnamed Notre Dame beat writer was quoted in the Iowa City Press-Citizen two days before the game described the apocalyptic future of Notre Dame football should the Irish fall to Iowa.

“A Notre Dame defeat at Iowa will mean the bursting of all the castles we have built,” he said. “It will mean the elimination of Rockne’s eleven as any sort of a championship claimant; the culmination of a great record; the collapse of a growing tradition; the casting down of a man who is rapidly gaining consideration as the wizard of modern football.”

On Oct. 8, 1921, no castles burst, a growing tradition did not collapse and Knute Rockne was not relegated to obscurity.

In fact, Rockne coached at Notre Dame until 1930 and won three more national championships.

The Old Gold scored all of its points in the first quarter. The difference was a 35-yard, drop-kicked field goal by Aubrey toward the end of the period.

The rest of the contest was tough sledding for both sides. A quick glance at the play-by-play from the Press-Citizen shows lots of 3- and 4-yard gains, fumbles and stalemates.

On paper, Notre Dame might have appeared victorious. The Irish completed 13-of-22 passes for 227 yards, while Iowa completed just one pass for 10 yards. Notre Dame had 22 first downs, Iowa had 14. The Irish rushed for 239 yards, the Hawkeyes 206.

Turnovers killed the Irish late in the game. Notre Dame’s final three possessions ended with interceptions in Iowa territory. Two by Lester Belding at the Iowa 13- and 43-yard line, and one by Aubrey at the Iowa 13-yard line.

The 1921 Notre Dame Football Review wrote “Notre Dame’s superiority was unquestioned and the mere fact that Iowa by sheer luck obtained three more points than did the better team, does not show even the remotest instance that this scant margin would determine Iowa the conqueror.”

One of the Hawkeye heroes that day was Gordon Locke. The gritty, curly-haired fullback from Denison scored Iowa’s lone touchdown on a plunge from the one-foot line. In the fourth quarter, Locke was injured and replaced by Craven Shuttleworth.

The day after the game, The Daily Iowan wrote that Locke was hospitalized the night after the game but “suffered no serious injury and was merely overworked.”

Aubrey wrote in his autobiography that this was the only instance of a player being removed due to injury the entire 1921 season and that Locke “battered his head against the Irish line so hard that he became slightly confused and wanted to whip the whole Notre Dame team.”

If you look at the few grainy photographs that exist from this day, you will probably notice something.

One Black man in a sea of whites.

That man was Fred “Duke” Slater, whom Aubrey described as a “giant of a man” from a town called Clinton on the banks of the Mississippi.

Slater’s skin color is one of two things that make him easy to spot in these photos. The other being that he was usually the only player on the field without a helmet. Iowa coach Howard Jones had a policy that no player stepped on the field without the proper equipment. In Neal Rozendaal’s book about Slater, he said that Slater would wear his helmet for the opening kickoff and then fling it toward the Iowa sideline and play without it.

Aubrey wrote that he doubted Slater’s powerful offensive charge had ever been equaled in the game to that point.

“My signal calling strategy was very simple,” Aubrey said. “I just called the old ‘21’ play which meant Locke over Slater and if that didn’t go I knew we were in for a hell of a game.”

Slater did not score any of Iowa’s 10 points that day, but it could be argued no one had a bigger impact. He was often lined up against multiple Notre Dame defenders and almost always prevailed.

The Iowa City Press-Citizen wrote about Rockne’s thoughts on Slater.

“Knute Rockne, coach of Notre Dame gave Slater credit for the only defeat the South Bend team has met in three years. Rockne said he put four men playing against Slater alone and yet the giant negro made such holes in the stiff Notre Dame line that Locke went through for long gains, often standing up straight.”

As I got older and started doing my own research on the 1921 team, I became fascinated by Duke Slater. Mostly because I couldn’t imagine the courage it took to be the only Black man in the stadium almost every time he stepped on the field.

I also found a photo from the Notre Dame game, thanks to my uncle G.K., that shows Slater lying on the ground. To his left, a pile of bodies. To his right, an expansive running lane.

One Irish defender is flying over Slater with a hand on an indistinguishable ball carrier. But the timing of the photo makes it appear that all Slater needed was an elbow to propel the man into the backfield.

The Old Gold finished the season 7-0 and outscored its opponents 185-36. The Hawkeyes finished 5-0 in the Big Ten (then called the Western Conference). Aubrey, Locke and Slater all were named All-Americans. All three men’s names are enshrined on the front of the Kinnick Stadium press box.

Iowa finished 7-0 the next season led by Locke, who was named a consensus All-American. Aubrey entered law school and coached for a few years. Glenn became the football coach at Parsons College in Fairfield, Iowa, and Duke Slater became the first Black lineman in the NFL and the first Black judge to serve on the Cook County Superior Court in Chicago.

In the 1960s, a ratings system called the Billingsley Report was created and retroactively awarded Iowa the 1921 national championship.

Iowa and Notre Dame did not play again until 1939. Eddie Anderson, who was on the 1921 Notre Dame team, was the coach of the legendary Iowa “Ironmen” of 1939 that starred Heisman Trophy winner Nile Kinnick.

Iowa and Notre Dame have not played since 1968. In 24 all-time meetings, Notre Dame won 13, Iowa 8, and three games ended in a tie.

So while the Iowa-Notre Dame rivalry is all but dead, that 1921 game – and season – remains an important piece of Iowa football – and my family’s – history.