Quinn Early determined to help two noble and important causes

By Pat Harty

IOWA CITY, Iowa – Quinn Early is on a mission that is inspired by his love for his mother, and for Hawkeye football.

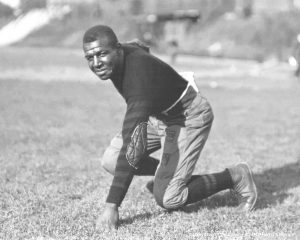

The former Iowa and NFL wide receiver is about to release a documentary on the life of Tipton native Frank Kinney Holbrook, who was the first African-American intercollegiate athlete at the University of Iowa, where he lettered in both football and track field in 1895 and 1896.

The documentary is titled the “The Shoulders of Giants” and money raised from the documentary will go to the Ann Early Intervention Foundation that funds research for Alzheimer’s, Dementia and other similar conditions, while also providing educational and financial support in the community.

Early’s mother, Ann Early, passed away in 2013 from Alzheimer’s, and Quinn Early is now using her memory, and her legacy, to promote a great cause.

Quinn Early was a guest on the Hawk Fanatic radio show and podcast on Wednesday and talked about the release of his documentary, and how it came to be.

Quinn and his mother were very close and she played a key role in his rise as an athlete, and in helping him become a man with high character and determination.

Sadly, Quinn has the misfortune of having watched a terrible disease ravage his other’s mind.

It crushed him emotionally, but it also lit a fire that burns brighter with each day.

Quinn Early is determined to make something positive out of a terrible situation in his life, and that’s a tribute to him, and to his mother.

He also is determined to shine a positive light on the Iowa football program’s long-standing history of promoting racial equality in college athletics.

And the timing couldn’t be better under the circumstances.

It has been almost a year since multiple former Iowa black players accused the Iowa football program of racial disparities.

Chris Doyle lost his job as Iowa’s long-time strength and conditioning coach as part of the fallout, and eight former black players have filed a federal law suit alleging that staff members mistreated black players.

The accusations are serious and disturbing and the lawsuit will go to trial in 2023.

So this controversy isn’t going away anytime soon.

And while the accusations can’t be ignored or dismissed, Iowa football has long stood for racial equality, and that shouldn’t be ignored or dismissed, either.

Iowa football needs to embrace its past and remind fans, and critics, that it has fought against racial discrimination pretty much since the beginning.

Holbrook played at Iowa at a time when most schools prohibited blacks from competing in athletics.

To put it in perspective, Wilbur Jackson was the first black player to be offered a football scholarship to the University of Alabama, but that milestone moment happened about 75 years after Holbrook had played at Iowa.

Jackson played at Alabama under Paul “Bear” Bryant from 1971-73, and by that time Iowa already had a long and distinguished history of supporting racial equality in athletics.

Duke Slater was a first-team All-American at Iowa in 1921 and would go on to become the first black lineman in the NFL and the second African-American judge in Chicago history.

Iowa now has dormitory named after Slater, and that’s where Early lived for part of his college career, but without knowing the significance of the name.

“What’s interesting is I lived in Slater Hall, and yet, I had no idea about the history,” said Early, who grew up in New York. “I was also 19 and 20 (years old), so I was more concerned with what my hair was looking like and talking to the ladies than I was about history.

“But as I’ve gotten older, I realize these people were pioneers, not just in history in general, but at the University of Iowa. And because of their example, people like me were able to follow through and do what I did.”

Iowa and Minnesota play for a statue of a bronze pig called Floyd of Rosedale, whose origin is rooted in racism.

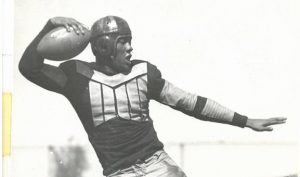

Ozzie Simmons was a star running back for the Hawkeyes in the mid-1930-s, but some opponents resented him simply because he was black.

Simmons was subjected to both verbal and physical abuse, and the situation became so volatile against Minnesota that the governors from both states got involved in hopes of keeping the peace in the emotionally charged days leading up to the 1935 game in Iowa City.

To help lighten the mood, Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson sent a telegram to Iowa Governor Clyde Herring on the morning of the 1935 game in which Olson offered to bet a prize Minnesota hog on the outcome of the game.

The loser would send the winner a prize hog, and Herring accepted the challenge. He then kept his promise after Iowa’s 13-6 loss by personally delivering a hog to Olson’s office.

A statue of a bronze pig called Floyd of Rosedale now goes to the winner of the Iowa-Minnesota game, but the statue represents more than just football.

It represents a time when Iowa football stood tall in the fight against racial discrimination when few others school were willing to take that controversial step.

Iowa football also has Hayden Fry as part of its rich legacy, and his history of promoting racial equality can’t be overstated.

Fry broke the color barrier in the Southwest Conference in the mid-1960s by recruiting Jerry LeVias to Southern Methodist University.

Fry had the courage to stand up against racial discrimination when most other head coaches were either too scared to do it, or were against doing it.

So from Frank Kinney Holbrook to Duke Slater to Ozzie Simmons to Hayden Fry, Iowa football has a proud history in the fight for racial equality and acceptance.

More times than not, Iowa football has been on the right side of racial controversies, and that never should be forgotten.

It should be celebrated and promoted, just like what Quinn Early is doing with his documentary on Frank Kinney Holbrook, who passed away of a heart attack in 1916 at the age of just 39.

Holbrook didn’t live long, but his impact will live on forever, with help from Quinn Early.