The James Speed case: A Sentinel Event at the University of Iowa

Editor’s note: Pat Collison is a retired ear, nose and throat doctor who was trained at the University of Iowa and now lives in Iowa City.

By Pat Collison

Special to Hawk Fanatic

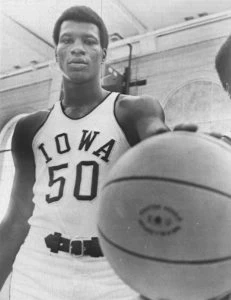

IOWA CITY, Iowa – James R. Speed was the most highly regarded college basketball player in the country when he enrolled at the University of Iowa for the 1970 fall semester. At Valencia High School in Shreveport, Louisiana Speed averaged 31.2 points and 19 rebounds a game and more than 80 schools vied to recruit him as a California junior college player before he signed with the Hawkeyes. Standing 6 foot 7 inches, he was quick and agile enough to play guard and he showed a remarkable shooting range. He was already being compared to contemporary NBA great Elvin Hayes, and later, George Gervin. Perhaps a more familiar measure of his potential would be to envision a bigger, stronger Michael Jordan.

Speed joined a program that was riding high, following on the heels of one of the most productive and entertaining teams in the history of Iowa basketball. The 1969˗70 squad (20-5, 14-0 Big Ten) was coached by the legendary Ralph Miller. They were nicknamed the “6-Pack” because only six players ̶ Chad Calabria, Glenn “Stick” Vidnovic, Dick Jensen, John Johnson, “Downtown Freddy” Brown, and “Supersub” Ben McGilmer shouldered all the playing time. Iowa set scoring records in the conference (102.9 points/game) and for the NCAA tournament (121-106 vs. Notre Dame in a Regional Consolation match-up). They fell to Jacksonville 104-103 on a last second tip-in by 7-footer Pembrook Burrows III. Johnson and Brown went on to long and successful NBA careers, but the only returning starter for the 1970 ̶ 71 season was Brown. Also, Miller unexpectedly resigned to coach at Oregon State that summer and assistant coach Dick Schultz took over. Still, expectations were high with the signing of James Speed and 7-foot Iowa native Kevin Kunnert.

Unfortunately, hope for continued success vanished before the 1970 season had even begun. After James began his classes at Iowa that fall, events took place that initially seemed innocuous, but rapidly progressed to become a personal tragedy for the young star and a sentinel event for the University of Iowa and its renowned health care system.

The clinical timeline is as follows: Early that fall Speed began complaining of what seemed to be a cold, for which team trainers dispensed decongestants. The symptoms persisted and by Thanksgiving week they became worse with the appearance of increasing headache and on Thanksgiving Day, toothache. He was examined by the oral surgery resident on call who noted cavities in several teeth. Codeine and aspirin were prescribed and a tooth extraction was scheduled for the next day. On Friday the 27th two teeth, probably upper molars, were removed uneventfully but that night Speed recalled feeling like “someone was standing over me and hitting me on the head with a hammer.” The next day another oral surgery resident examined Speed and found the extraction site to be healing normally, but because of severe headache administered intravenous Demerol and Phenergan and sent James home on oral Dilaudid, a potent narcotic analgesic.

Speed spent Sunday in bed, unable to find relief from an even more intense headache. Because of malaise and nausea he stopped eating. On Monday morning Speed returned to the Oral Surgery Clinic where again nothing worrisome was found at the extraction site. Having no explanation for his patient’s symptoms, the resident oral surgeon prescribed a placebo (vitamin pills). Again unable to sleep and writhing in pain at home, Speed then sought help at the Field House from Coach Schultz who immediately had a trainer take him to Student Health. Team physician Dr. William D. “Shorty” Paul noted swollen eyelids in addition to the other symptoms and admitted him to the infirmary, recommending intravenous fluids and Bufferin. No tests were ordered, though Dr. Paul considered “mono, brain abscess, septicemia” in his differential diagnosis. Later an on-call physician examined James and described petechiae (superficial hemorrhage) on his soft palate and eyelid erythema (redness), ordering Phenergan for nausea and, for the next morning, a monospot test (for mononucleosis), complete blood count, and urinalysis. That night when he went into the bathroom James realized that his eyes were nearly swollen shut and called for help. One of the medical residents responded by telling the nurse, “Marie, Jim Speed has sore eyes. Give him a Seconal (a sedative) and call me in the morning.” It was about this time when the first temperature elevation was recorded, up to 104 degrees, and a “picket fence” fever pattern persisted after that.

The next morning Speed exhibited nuchal rigidity (neck stiffness, indicative of meningitis) and bilateral proptosis (eyeballs protruding from their sockets). Dr. Paul consulted neurology which promptly transferred the patient to their department where plain sinus x-rays showed ethmoid opacification, a finding consistent with infection involving the sinus cavities between the eyes and the nose. A diagnosis of cavernous sinus thrombosis was made. This rare complication occurs when an infected blood clot obstructs the venous outflow from the eyes at the base of the brain. The condition is exceedingly uncommon: only four similar cases out of more than 2.5 million patient encounters were recorded at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics between 2002 and 2017. It should be understood that in 1970 this diagnosis had to be made based on clinical findings alone. Computed tomography was not invented until 1972 and magnetic resonance imaging became available in 1977.

An ophthalmology exam recorded Speed’s visual acuity as “no light perception” for the right eye and markedly decreased vision for the left. Intravenous ampicillin and heparin (an antibiotic and an anticoagulant) were administered and that evening Dr. Brian McCabe, Chairman of the Department of Otolaryngology, performed an emergency sinus surgery, most likely bilateral external ethmoidectomy, in which the source of the infection was eradicated through incisions between the eyes and the nose. After this procedure, James’ medical condition, which was by then grave, stabilized, and he was discharged from University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics one month later, totally and permanently blind (Speed vs. State 1976).

Naturally, James struggled at first to accept these life-altering events and cope with his sudden and profound disability. The University of Iowa honored his athletic scholarship and a trust fund was established by the athletic department to defray medical and rehabilitation costs. Speed tried to resume academic life on campus, but his celebrity, and especially the form it took, made him uncomfortable and he complained that he felt too distracted to study successfully. He did maintain a close relationship with his teammates and attended a number of Iowa home games that winter. His dignified presence courtside made him a heartbreakingly sympathetic figure to Hawkeye fans. The team, without its standout recruit, struggled through a 9-15 season.

In 1973, the malpractice trial that resulted from this case was closely watched. It is significant in several respects. Through his attorney James Hayes, plaintiff Speed sued the State of Iowa before Judge Harold Vietor for $5,000,000 under the Tort Claims Act. Dr. Paul (internal medicine faculty), two oral surgery residents, and two on-call medical residents were named as defendants for providing negligent care. The court found Dr. Paul negligent for not ordering appropriate tests as well as one of the oral surgery residents for not seeking specialty consultation, awarding $750,000 in damages. At the time this was the largest malpractice award in Johnson County history and the first time University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics had been sued successfully.

The State appealed, raising issues of negligence and proximate cause. Judge Vietor had determined that an earlier correct diagnosis would have led to the administration of intravenous antibiotics and prevented Speed’s blindness. The State countered by citing an imputed “old school” practice of quick use of antibiotics versus a “modern school” approach of withholding antibiotics until a specific organism was identified, suggesting that early treatment would have gone against current medical standards and endangered the patient. The court rejected this argument.

The defendants also argued the so-called “locality rule” by questioning the plaintiff’s experts’ legitimacy, given that they did not practice in the State of Iowa. Up to this time expert witnesses for the plaintiff were required to reside in the state, making it difficult to find physicians who were willing to testify against their colleagues. These experts came from Northwestern University, the University of Pittsburgh, and New York University Medical School. One of them, Dr. Thomas Yarington referred to the Speed case in a review article on cavernous sinus thrombosis he wrote a few years later (Yarington 1977:457). The court rejected the locality rule argument also, setting a new precedent in light of modern conditions of medical education and practice. This approach recognized that hospitals and physicians under similar circumstances are held to the same standard of care, rather than by a specific locality. It was a victory for scientific universalism over specifism, and nation-wide standards over “states’ rights” medicine. The judgment was upheld. Judge Vietor explained that he didn’t consider Speed’s potential earnings as an NBA player because he was so early in his career, while acknowledging his exceptional ability, discipline, and desire.

Dr. Paul, who was in his 80s when the James Speed case occurred, retired the following year. He was the only University of Iowa faculty member found guilty of negligence, and this represented a tragic end for an otherwise exemplary career. He served as U. of I. team physician from 1939 to 1971, a position for which he steadfastly refused payment. He was said to have treated Hawkeye athletes rather roughly, although no one doubted his dedication or integrity. His reliable presence on the sidelines or courtside earned him the respect of Iowa fans, yet the sight of this diminutive physician attending to much larger players and then shoving them brusquely back into the game was a source of amusement. “Shorty” Paul came by his nickname honestly, standing only 4 feet 9 inches in height. Positioned next to his oversized charges, the contrast was striking and endearing to Hawkeye fans. Some grumbled about the seemingly lackadaisical way he strolled out onto the field to examine a fallen player, not realizing that his mobility was impaired by orthopedic problems of his own.

Dr. Paul was a respected faculty member in the Department of Internal Medicine where he specialized in rheumatology. An aggressive, inquisitive clinician, he is considered a pioneer in sports medicine and rehabilitation and made contributions in such disparate fields as endoscopy, electrocardiography, and the use of new drugs such as curare and insulin. He was also the first medical director of the U. of I. Physical Therapy Department, implemented in 1942 at the request of the U.S. Army. The program was offered free by the university as part of its contribution to the war effort. Initially only women age 19 to 45 who were not already nurses were eligible.

Many of Paul’s rheumatology patients and student athletes experienced joint and muscle pain, for which he prescribed aspirin. Some, including his colleague Kate Daum, head of the Department of Nutrition, complained of gastrointestinal side effects. In an effort to alleviate these problems Dr. Paul collaborated with Dr. Joseph Routh, PhD, to successfully compound buffered aspirin (Bufferin). Bristol-Myers marketed this product and the developers themselves never patented or profited from their work. Although he didn’t publish all his findings, Paul was an astute enough observer to recognize that patients who took a daily aspirin rarely had heart attacks. The protective effect of aspirin was unknown at that time.

Descriptions of Paul’s life published by the University of Iowa, as with most alumni sources, are hagiographic in nature, reading like the Lives of the Saints. He is portrayed as a committed physician with a heart of gold despite his rough bedside manner. These accounts never mention the Speed case which essentially ended his long, productive career.

So how did the rest of James Speed’s life play out after he lost his eyesight? The best source of this information is his wife Sylvia, who has lived in Las Vegas from the time of their marriage in 1975 to the present. She graciously agreed to meet with me in her home during a recent visit to discuss her memories of their life together. James died in 2011 at age 62. She remains actively involved in her community, that day having just finished helping voters register and cast their ballots in the recent election.

James and Sylvia met at the Iowa Commission for the Blind in Des Moines where James was enrolled in January 1971, shortly after he was discharged from University of Iowa Hospitals where he had recovered from his acute illness. Sylvia was working there as a rehabilitation counselor, her work focused on improving clients’ mobility and independent transportation skills. She recalls him appearing sullen and depressed at first, but eventually becoming engaged in the training program, accepting his situation with resolve and even humor. He learned Braille, although it was difficult to master as an adult, and he embraced the other adaptive strategies that were necessary to cope with his disability. They became friends during his stay in Des Moines.

While James made an unsuccessful attempt to resume his studies in Iowa City, Sylvia worked in Washington, D.C. Several years later she took a position at the Nebraska Services for the Blind and Visually Impaired where the two of them re-connected. James intended to continue his education in Lincoln, but the first few winter snowstorms convinced him that the Midwest was not the place for him. He decided to move to Las Vegas where he had relatives and had participated in road games as a junior college player. Sylvia joined him there and they were soon married. Both of them found Las Vegas to be a challenging place to live at the time. Sylvia likened it to a “Mississippi of the West” in terms of race relations, and the lack of public transportation presented significant obstacles for them, who were by then raising a family.

After attending University of Nevada-Las Vegas briefly, James completed his college education with a bachelor’s degree from Southern University in Louisiana and a Master’s in Rehabilitation Counseling from Grambling. For a time he served as an assistant basketball coach at The College of the Ozarks, and provided color commentary on the radio during their games. Additional obstacles awaited him when he returned to Las Vegas. Unable to find work in rehabilitation counseling there, James secured a position in Kansas City. Sylvia stayed in Las Vegas with their children and describes this period in the marriage as a “long distance relationship” which nevertheless held together.

Concerning the events that led to his blindness, Speed didn’t dwell on the details or bring the subject up unless asked, preferring a more future-oriented outlook. As his wife put it “You have two choices: you can move forward or you can stay stuck.” Most of all, he seemed determined not to let his blindness be the thing that defined him. He repeatedly adapted to and overcame the obstacles he faced, countering them with strength of will, resilience, and self-deprecating humor. As the elite athlete that he was, Speed made a concerted effort to stay in shape through regular exercise, even after losing his eyesight. He liked to go on runs around the neighborhood with Sylvia acting as his guide. When she became pregnant and was no longer able to run with him, they attached a rope to their car and she would drive around the block with him trailing just behind. He also enjoyed swimming and working out at a local gym. A great outside shot in his playing days, he found a way to shoot baskets by having a friend tap the rim with a metal rod so he could judge how far and which direction he was from the basket.

When asked if her husband was aware that not all Iowans were sympathetic in the aftermath of his illness, Sylvia responded with a knowing, “Oh yeah.” Her matter-of-fact reaction to the resentment provoked by the 1973 malpractice judgment was not one of outrage but more chagrined resignation. In fact, her assessment of those who begrudged Speed’s monetary award was more than generous: “People respond to tragedy in different ways. They felt we should have been grateful for the outpouring of kindness and not have sued.” Although Speed and his attorney Jim Hayes were both exposed to bigoted remarks about the case, Speed did not let these attitudes crush his optimistic, outgoing demeanor, nor Hayes his advocacy.

Speed was a gregarious person who kept many long-term friendships. He liked to call up old teammates and other associates from his days as an athlete, basketball coach, and sports commentator. He tended to ignore time zone differences, but the long phone calls punctuated by laughter indicated that no one seemed to mind. His love of conversation was not limited to famous athletes; he was “a person who would talk to anyone”, including strangers he met on the bus, in the casinos he frequented, and in restaurants. He was an enthusiastic fan of all sports, especially basketball, and followed games and sports talk shows on TV and radio, sometimes several at once.

After he returned to Las Vegas from Kansas City, James was again unable to secure a position as a rehabilitation counselor. Refusing to succumb to this disappointment he obtained his real estate license in 2005 at age 56 and worked in this field as a referral realtor. His engaging personality served him well in this capacity, although this period encompassed the collapse of the real estate market throughout the country in the crash of 2008, particularly in Las Vegas. As bad as it was, one might wonder if Speed thought to himself, “I’ve been through a lot worse than this.” He threw himself enthusiastically into this new endeavor and continued working until his terminal illness from liver cancer in 2011.

When Speed met with an Iowa City Press Citizen reporter in 1984, he asserted that this was the last that he would say publicly about his blindness and the circumstances surrounding it. When asked at the end of the interview, “After what you’ve been through, you don’t seem bitter. Why not?” Speed’s characteristically understated answer was “It’s bad enough being blind without being bitter” (Cassiere 1984:1).