Story behind Floyd of Rosedale always deserves being told

By Pat Harty

IOWA CITY, Iowa – The football rivalry between Iowa and Minnesota probably doesn’t get much attention from those not affiliated with or loyal to one of the two schools.

And it’s easy to see why.

Iowa has won the last eight games in the series, which dates back to 1891, and Minnesota hasn’t been relevant in football in over a half century.

The Gophers haven’t won a Big Ten title since 1967, which is 13 years before current Minnesota head coach P.J. Fleck was even born.

Minnesota used to be a national power, but that was before central air conditioning had become common, and before the Beatles and the Rolling Stones had come along.

Iowa has been way more successful than Minnesota over the past 40 years, but the Hawkeyes certainly have their share of problems, most notably a struggling offense that has been decimated by injuries to key players.

The ongoing Brian Ferentz saga also continues to be a main storyline, and it has gained momentum after the offense had just 37 passing yards in the 15-6 win at Wisconsin last Saturday.

So, yes, there is plenty about this long-standing border rivalry that leaves much to be desired as evidenced from the 31-point over/under point total for Saturday’s game, which is the lowest in 20 years.

But where it has no equal is the story about why the teams play for a bronze statue of a pig named Floyd of Rosedale.

College football is filled with rivalries in which teams compete for some type of object, whether it be a statue, trophy, or plaque.

And each is special in its own way.

But the story behind Floyd of Rosedale ranks above all others, at least in my opinion, and I’m willing to recognize that I might be a little biased.

It ranks on top of all trophy games because of what it represents, and because of the role that Iowa played in the events that led to Floyd’s creation in 1935.

Iowa represents the good side of the story, the side of equality and human decency, while the Gophers are sort of the villain.

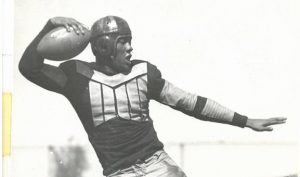

Floyd’s story is rooted in racism and hate, but through it all came a story of hope and inspiration, albeit at the expense of halfback Ozzie Simmons.

He was the inspiration for Floyd as the focus of Minnesota’s rage simply because he was a black man playing a white man’s game at the time.

Simmons also played it quite well as an explosive and slippery running back from Fort Worth, Texas, and his success on the field fueled his haters even more.

The level of Minnesota’s hate toward Simmons was on full display in the 1934 game when the Minnesota players brutalized him with late hits and other cheap shots.

Simmons took such a beating that he had to leave the game multiple times.

Minnesota would go on to win 48-12 in Minneapolis, but the fallout from the game would change the series forever.

Iowa fans were so upset with how Simmons was treated in 1934 game that emotions were threatening to boil over in the days leading up to the 1935 game in Iowa City.

Minnesota head coach Bernie Bierman received a bunch of threatening letters from Iowa fans saying that they wouldn’t tolerate Simmons being abused on their home field.

The day before the game, Iowa Governor Clyde L. Herring told reporters, “If the officials stand for any rough tactics like Minnesota used last year, I’m sure the crowd won’t.”

The concern was that some Iowa fans would rush on to the field if they saw Simmons being mistreated.

But fortunately, cooler heads would prevail, and former Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson is to thank for that because he came up with the idea that helped to defuse a scary and potentially dangerous situation.

The day before the 1935 game, Olson sent a telegram to Governor Herring on game-day morning, which read, “Minnesota folks are excited over your statement about Iowa crowds lynching the Minnesota football team. I have assured them you are law abiding gentlemen and are only trying to get our goat…I will bet you a Minnesota prize hog against an Iowa prize hog that Minnesota wins.

A tradition was born as the 1935 game was played without incident, and without Simmons getting injured.

Minnesota won 13-6, and then would go on to win its second straight national championship that season.

After a 4-0 start, Iowa finished the 1935 season with a 4-2-2 record, but that team will always be remembered for its role in helping to establish a tradition in college football whose message goes so far beyond the game itself.

Ozzie Simmons was known as the “Ebony Eel” for how he slithered past his opponents on the field.

That nickname, obviously, wouldn’t work today because so much has changed for the better since Simmons played for the Hawkeyes nearly 90 years ago.

So, while much of the nation probably doesn’t care about the outcome of Saturday’s game at Kinnick Stadium, the story behind Floyd of Rosedale is something Iowa fans should care about and cherish forever.

The Iowa football program suffered a public relations nightmare after multiple players in the summer of 2020 accused Kirk Ferentz’s program of racial discrimination and bullying.

A program that had long stood for equality and inclusivity was suddenly being judged entirely different, and it was sad to see.

Kirk Ferentz vowed to fix the culture, and more than three years later, most signs point to that happening.

At some point this week, the newcomers on the Iowa football team will have learned about the story behind Floyd of Rosedale if they haven’t already.

They will have learned that Ozzie Simmons showed tremendous courage just by playing for the Hawkeyes during that tumultuous time, and that his teammates, coaches and fans showed kindness and fairness by embracing him at a time when most teams and most fan bases wouldn’t even consider it.

Iowa football has been at the forefront of racial equality in their sport.

Tipton native Frank Kinney Holbrook was the first African American intercollegiate athlete at the University of Iowa and one of the first African Americans to participate on an American college varsity athletic squad. He played on the Iowa football team team and lettered in both football and track and field in 1895 and 1896. Holbrook was Iowa’s leading scorer in 1896 and led the Hawkeyes to their first football conference title in school history.

To help put the timing in perspective, running back Wilbur Jackson was the first black student-athlete to be offered a scholarship from the Alabama football team, but that didn’t happen until 1970.

Floyd of Rosedale is so much more than just a trophy, and each year we’re reminded about that as the Hawkeyes and Gophers face each other in what will remain as a protected rivalry, even as the Big Ten expands from coast to coast.

And though Floyd has a strong connection to both universities, he has spent the past eight years living in Iowa City, and that probably has Ozzie Simmons looking down and smiling.

Minnesota vs. Iowa

When: Saturday, 2:33 p.m.

Where: Kinnick Stadium

TV: NBC/Peacock

Radio: Hawkeye Radio Network

Series record: Minnesota leads, 62-52-2

In Iowa City: Iowa leads, 32-23-1

Last meeting: Iowa won 13-10 on Nov. 19, 2022 in Minneapolis.